Throughout most of history, artists have depicted epidemics from the profoundly religious framework within which they lived. In Europe, art depicting the Black Death was initially seen as a warning of punishment that the plague would bring to sinners and societies. The centuries that followed brought a new role for the artist. Their task was to encourage empathy with plague victims, who were later associated with Christ himself, in order to exalt and incentivise the courageous caregiver. Generating strong emotions and showing superior strength overcoming the epidemic were ways to protect and bring solace to suffering societies. In modern times, artists have created self-portraits to show how they could endure and resist the epidemics unfolding around them, reclaiming a sense of agency.

Through their creativity, artists have wrestled with questions about the fragility of life, the relationship to the divine, as well as the role of caregivers. Today, at a time of Covid-19, these historical images offer us a chance to reflect on these questions, and to ask our own.

Plague as a warning

At a time when few people could read, dramatic images with a compelling storyline were created to captivate people, and impress them with the immensity of God’s power to punish disobedience. Dying of the plague was seen not only as God’s punishment for wickedness but as a sign that the victim would endure an eternity of suffering in the world to come.

|

| This early illustrated manuscript depicts the Black Death |

This image is one of the first Renaissance Art representations of the Black Death epidemic, which killed an estimated 25 million people in Europe during its most devastating years. In this illustrated manuscript painted in Tuscany at the end of the 14th Century, devils shoot down arrows to inflict horror upon a tangled mass of humanity. The killing is portrayed in real time, with one arrow about to hit the head of one of the victims. The symbol of arrows as carriers of disease, misfortune and death draws on a rich vein of arrow metaphors in the Old Testament and Greek mythology.

In this understanding of the plague, the apocalypse is laid on for humanity’s ultimate benefit

Australian art historian

Dr Louise Marshall argues that, in illustrations like this, devils are subcontracted by God to castigate humanity for their sins. Medieval people who saw this image would be terrified by the winged creatures because they believed devils had emerged from the underworld to threaten them with incredible powers.

This portrayal shows us the devil’s slaughter as indiscriminate, emerging out of the corrupted atmosphere of the dark clouds to target the whole community. “The image acts as a warning about not only the loss of a community but the end of the world itself,” says Dr Marshall. In this understanding of the plague, the apocalypse is laid on for humanity’s ultimate benefit, so that we can learn the error of our ways and fulfil the divine will by living a true Christian life.

|

| Plague is portrayed as a punishment in this 14th-Century illustration |

The plague punishment narrative also forms part of the story of the liberation of the Jewish people from Egypt, retold by Jewish communities every year at Passover. This image of one of the 10 plagues brought down on the guilty Egyptians comes from a 14th-Century

illuminated Haggadah. The manuscript was commissioned by Jews in Catalonia to use at their annual Passover meal. Here, the Pharaoh and one of his courtiers is smitten by boils for their sins of oppressing the Israelite slaves who the Egyptians claimed were swarming like insects. Professor of religion and visual culture,

Dr Marc Michael Epstein, highlights “the extreme punishment revealed in the detail of this image, the three dogs licking their sinful Egyptian owners’ festering sores”.

Artworks created during times of plague reminded even the most powerful that their life was fragile, temporary and provisional. In many plague paintings there is an emphasis on the suddenness of death. The image of the danse macabre is repeated, where everyone is encouraged by the personification of death to dance to their grave. There is also extensive use of the hourglass to warn believers that they had only limited time to get their affairs and souls in order before the plague might cut them off without warning.

Plague inspiring empathy

There was a dramatic development in plague art with the creation of Il Morbetto (The Plague), engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi in the early 16th Century, based on a work by Raphael.

|

| This 16th-Century engraving is by Raimondi |

According to US plague art historian,

Dr Sheila Barker, “what is significant about this tiny image is its focus on a few individuals, distinguished by their age and gender”. These characters have become humanised, compelling us to feel compassion for their suffering. We see the sick being given such tender care that we feel we too must act to relieve their pain. Here, a work of art has the potential to convince us to do something we may be afraid of doing – taking care of diseased and contagious souls.

This shift in plague art coincided with a new understanding of public health. All members of society deserved to be protected, not just the wealthy who could escape to their country villas. Doctors who fled the city for their own safety were to be punished.

This empathy theme was further developed in the 17th and 18th Centuries, with the closer alignment of the Catholic Church with a public-health agenda. Plague art began to be displayed inside churches and monasteries. Sufferers of the plague were now associated with Christ himself. Dr Barker argues that the purpose behind this identification was “to convince the friars to overcome their fear of the putrid smell of the dying body and the immensity of death by learning to love the contagious victims of the plague”. Those who cared for the sufferers potentially sacrificed themselves and were therefore exalted by being portrayed as saint-like.

|

| Poussin painted The Plague of Ashdod in 1630-31 |

Healing power

In the 17th Century, many people believed that imagination had the power to harm or heal. The French artist Nicolas Poussin painted The Plague of Ashdod (1630-1631) in the middle of a plague outbreak in Italy. In a recreation of a faraway tragic biblical scene, which provokes feelings of horror and despair, Dr Barker believes that “the artist wanted to protect the viewer against the very disease the painting depicts”. By arousing powerful emotions for a distant sorrow, viewers would experience a cathartic purge, inoculating themselves against the anguish that surrounds them.

|

| Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s 1892 artwork shows a warrior resisting smallpox demons |

The plague of smallpox devastated Japan over many centuries. An artwork created in 1892 depicts the mythical Samurai warrior Minamoto no Tametomo resisting the two smallpox gods, variola major and variola minor. The warrior, known for his endurance and fortitude, is portrayed as strong and confident, clothed with viscerally red ornate garments and armed with swords and a quiver full of arrows. In contrast, the fleeing, frightened, colourless smallpox gods are squeezed helplessly into the corner of the image.

Navigating pain through the self-portrait

Modern and contemporary artists have created self-portraits to make sense of their own plague suffering, while simultaneously contemplating the transcendent themes of life and death.

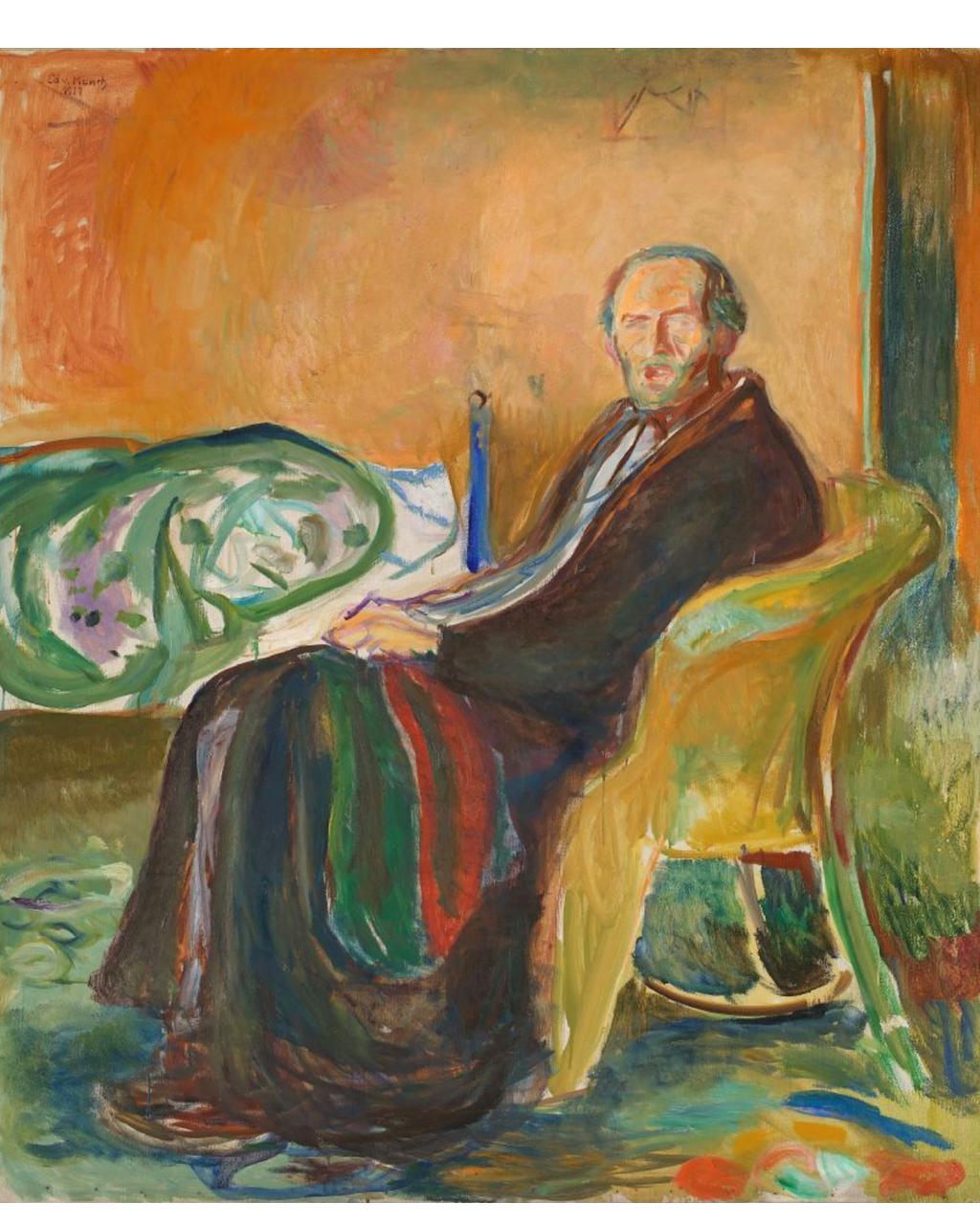

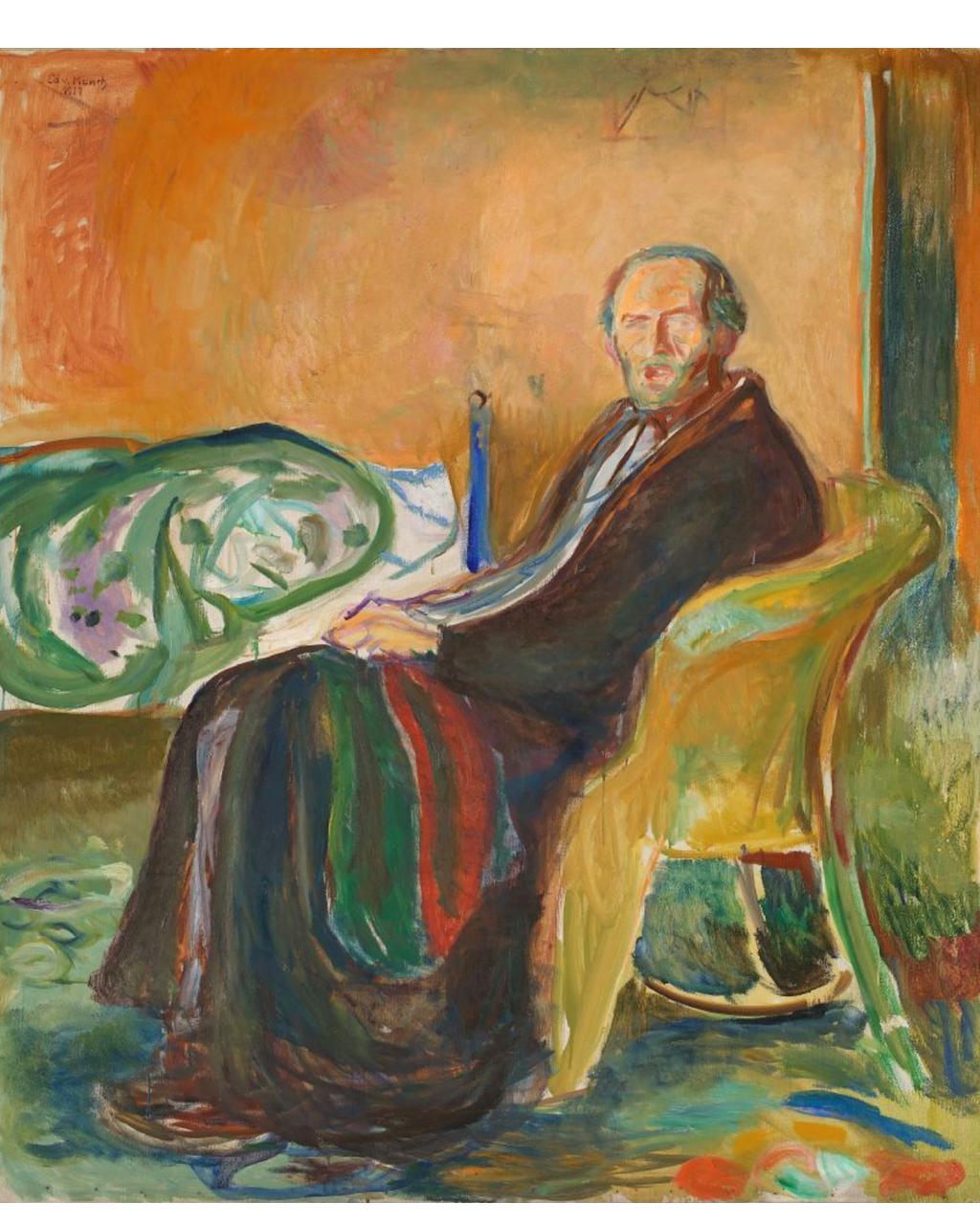

|

| Edvard Munch’s Self-portrait with Spanish Flu (1919) expresses the artist’s own pain |

When the Spanish Flu hit Europe just after World War One, Norwegian artist Edvard Munch became one of its victims. While his body was still grappling with the flu, he painted his trauma – pale, exhausted and lonely, with an open mouth. The gaping mouth echoes his most famous work, The Scream, and perhaps depicts Munch’s difficulty breathing at the time. There is a strong sense of disorientation and disintegration, with the figure and furniture blending together in a delirium of perception. The artist’s sheet looks like a corpse or a fitful sleeper, tossing and turning in the night. Unlike some of Munch’s previous depictions of illness, in which he portrays the sick person’s loved ones waiting with anxiety and fear, the artist here portrays himself as the victim, who has to endure this plague isolated and alone.

US academic

Dr Elizabeth Outka tells BBC Culture: “Munch is not just holding a mirror to nature, but also exercising some control through reimagining it.” Outka believes that art serves as a coping mechanism here for both the artist and viewer. “The viewer may feel a profound sense of recognition and compassion for Munch’s suffering, which can in some way help to heal their distress.”

|

| Egon Schiele’s The Family, 1918, is full of anguish |

In 1918, Austrian artist Egon Schiele was at work on a painting of his family, with his pregnant wife. The small child shown in the painting represents the unborn child of couple. That autumn, both Edith and Egon died from the Spanish Flu. Their child was never born. Schiele attached great importance to self-portraits, expressing his internal anguish through eccentric body positions. The translucent quality of skin is raw, as if we are given a glimpse of their tortured insides, and the facial expressions are vulnerable while simultaneously resigned.

David Wojnarowicz was a US artist who created a body of Aids-activist work, passionately critical of the US government and the Catholic Church for failing to promote safe-sex information. In a deeply personal, untitled self-portrait, he reflects upon his own mortality. About six months before he died of Aids, Wojnarowicz was driving through Death Valley in California and asked his travelling companion Marion Scemama to stop. He got out of the car and furiously started to scrape the earth with his bare hands, before burying himself.

As in the self-portrait by a flu-stricken Munch,

Dr Fiona Johnstone, a contemporary art historian from the UK, sees this work as David Wojnarowicz attempting to assert agency. “Here David takes control of his own fate by preempting it, wrestling back control of his illness by performing his own burial,” she says.

|

| In this untitled self-portrait, David Wojnarowicz reflects on his own mortality |

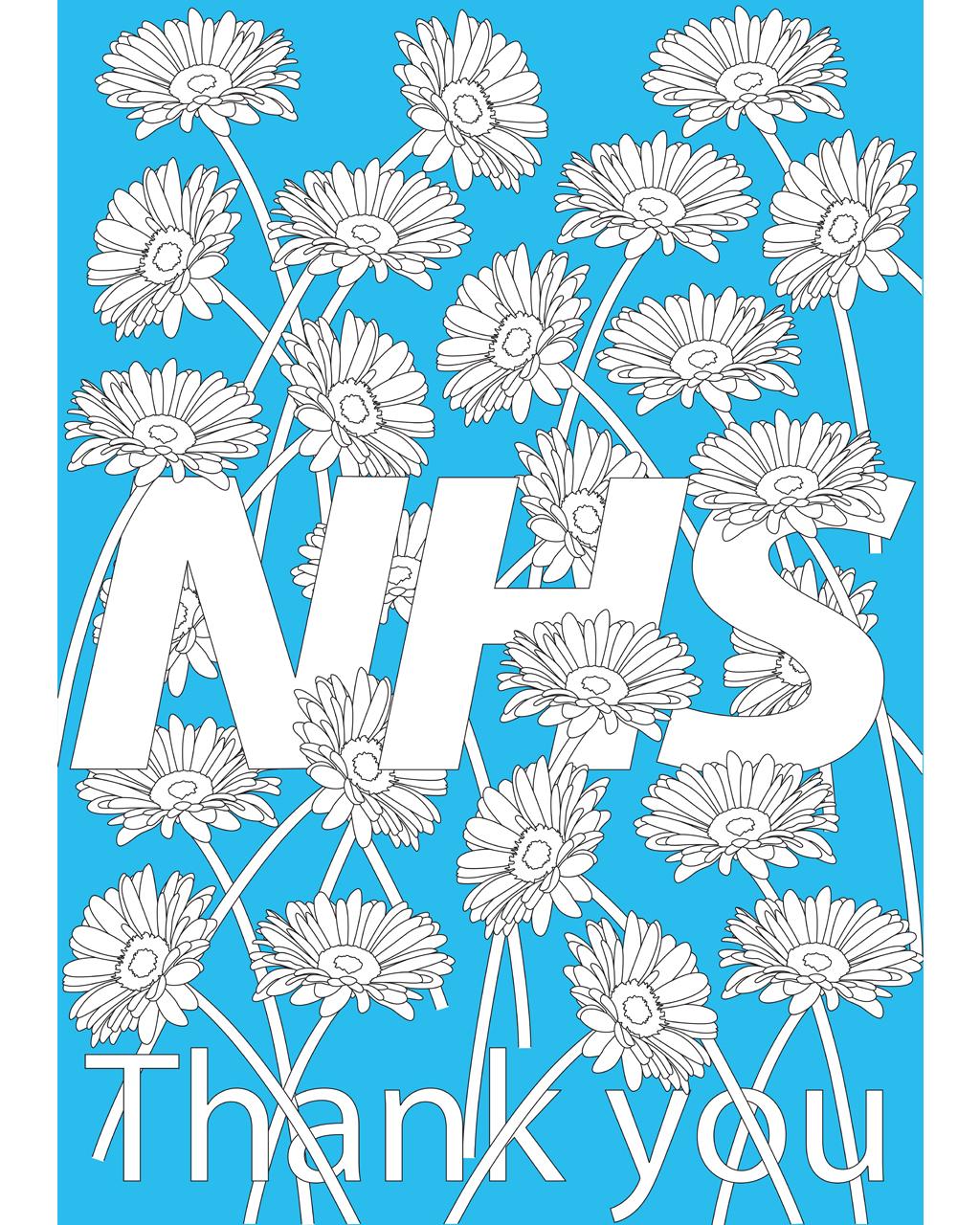

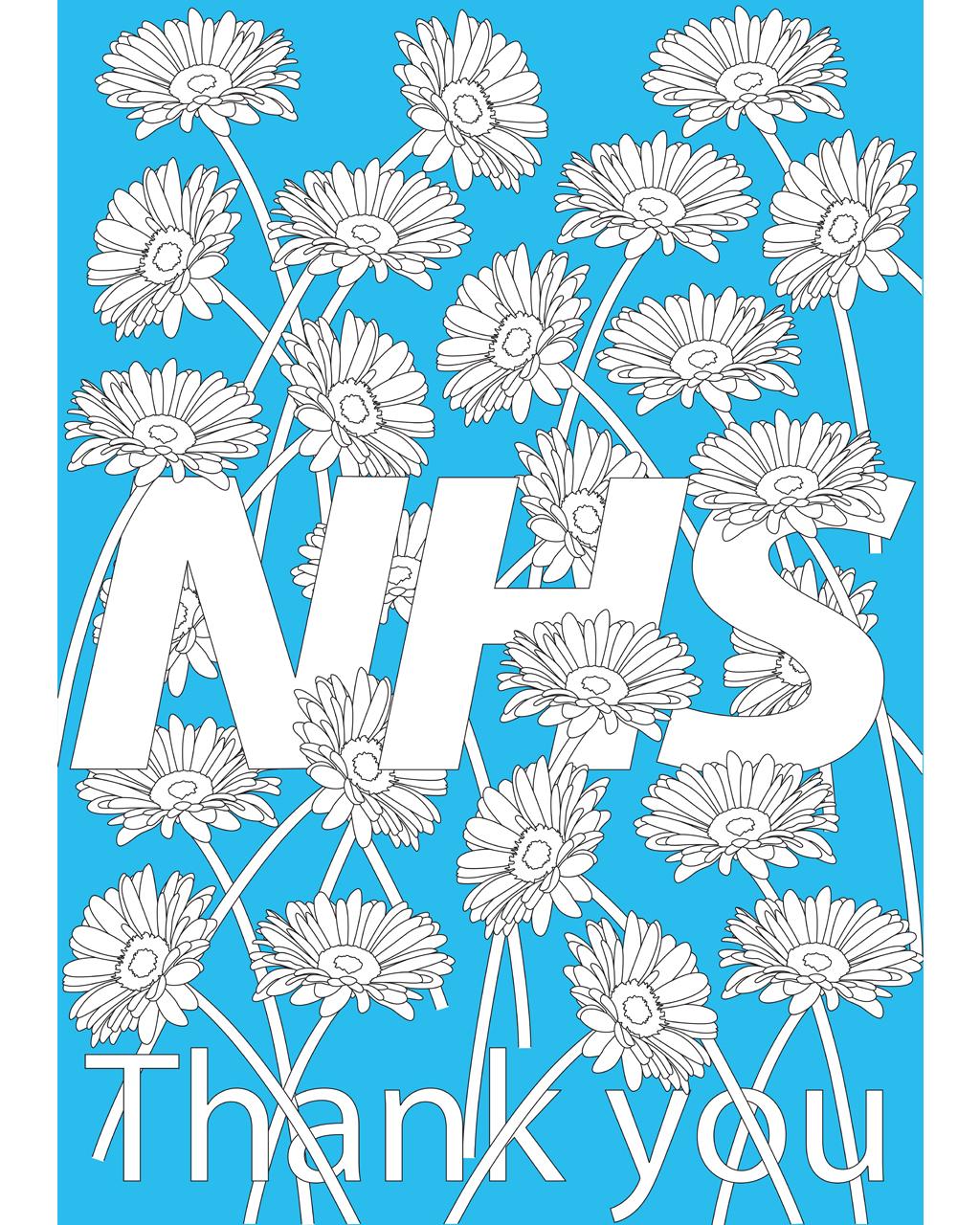

Today’s digital platforms are enabling artists to respond to the Covid-19 crisis by expressing and sharing in real time. The Irish-born artist Michael Craig-Martin has created a Thank You NHS flower poster. We are encouraged to co-create the artwork by downloading it, colouring it in, and then collaborating by displaying it in our window.

|

| Michael Craig-Martin is among the many artists who have been inspired by the current pandemic |

In countries across the world, artists are slowly making sense of the coronavirus and the self-isolating response in countries across the world. Contemporary art historians will be eagerly awaiting their work. We who are living through this modern-day plague will engage with these emerging images; they might even regain some control over an experience that threatens so much of humanity and our globalised lives.