In a possible first, a giant, faraway planet may have been caught in the act of growing moons.

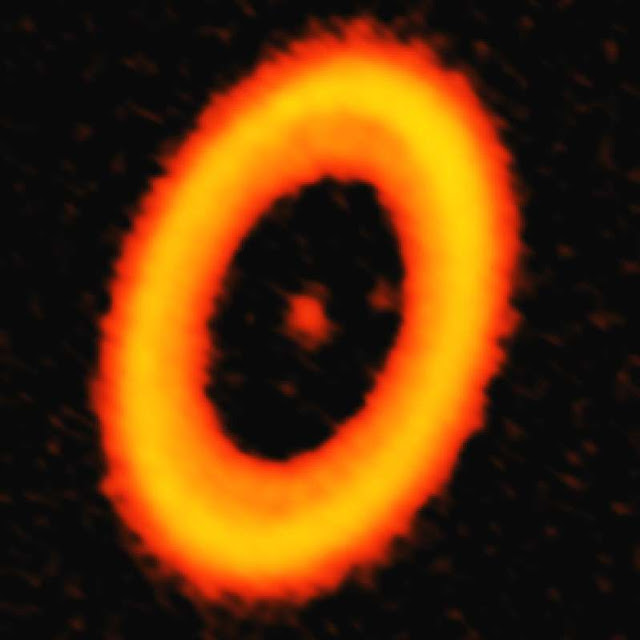

Seen in an image from the ALMA Observatory in Chile, the young planet orbits a small star roughly 370 light-years away, and it appears to be swaddled in a dusty, gassy disk—the exact type of structure scientists think produced Jupiter’s many moons billions of years ago. (Tour the moons of our solar system with our interactive atlas.)

“It’s quite possible there might be planet-size moons in formation around it,” study leader Andrea Isella of Rice University says in a statement.

“It’s certainly plausible that giant planets could have giant moon-forming disks around them,” says Stanford University’s Bruce Macintosh of the observation, published this week in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. “It’s an intriguing and quite possible result.”

Sean Andrews of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics agrees, adding that he is optimistic that the image is a first of its kind.

“If the result holds up,” he says “this will be an important ‘first strike.’”

Spin right ‘round

Astronomers have seen many similar dusty clouds surrounding stars. Called circumstellar disks, these structures are the milieu in which planets form—although the exact process by which worlds emerge from the dust is unknown. In some cases, astronomers think they can see newborn planets plowing lanes into these circumstellar disks, and ALMA has captured many images of these nascent planetary fingerprints.

But until now, no one had seen a dusty disk surrounding a planet itself; it’s hard enough to directly image planets beyond our solar system, let alone see the diffuse clouds of debris hugging younger, giant worlds.

Isella and his colleagues studied one dust-encircled star system, called PDS 70, using data gathered in 2017 by ALMA, an array of 66 radio dishes sprinkled over a patch of the Atacama desert. The star system includes a Jupiter-size planet called PDS 70b, which has vacuumed up a gap in the dusty shroud surrounding its small, six-million-year-old home star. Another planet, called PDS 70c, traces a path near the inner edge of the gap, at roughly the same distance from its star as Neptune is from the sun.

Initially, the hazy area around PDS 70c looked like a faint arm of gas. But this year, when the team reprocessed the ALMA data using a slightly different method, the irregularities resolved into a dust ring. Isella and his colleagues interpret the newly processed image as depicting a circumplanetary debris disk, the type of structure from which moons grow and burgeoning planets siphon material.

“We believe that Jupiter’s moons formed in a disk around the young Jupiter, and that circumplanetary disks play an important role in the formation of planets,” he says.

A faint disk of dust surrounds a large planet, possibly giving rise to a new moon, in an illustration of the star system PDS 70.

Straight to the point

But it’s not a rock-solid detection yet.

“There are certainly some puzzling aspects of these results,” Andrews says. He notes inconsistencies between observations made at different wavelengths, which produce slightly different images of the disk swirling around the star. When viewed by ALMA, that disk clearly contains a point source that looks like a planet: PDS 70c. But when studied in shorter, infrared wavelengths, that point source becomes much more diffuse.

“The environment around ‘c’ appears pretty complicated,” Andrews says.

Isella notes that “the ALMA detection is quite faint,” and he says that the team is working on confirming their result with additional observations.

“We have an ongoing ALMA program to re-observe this system and measure the orbital motion of the circumplanetary disk,” he says. “So, stay tuned.”